Documents have layers. First we see the words actually written on the paper. Beneath that surface lie the meanings those words had in their particular time and place. As we probe the record further, we discover layers of context created by law, custom, religion, and other social frameworks. A well-analyzed record will create more questions than it answers. It should also suggest more pathways we might take in our efforts to understand that corner of the past.

CASE AT POINT

Allison Graves found a curiously layered record in a Georgia courthouse. It appeared in a deed book, although it was not a deed. It hints at kinships but identifies none of them. It suggests the likelihood of many other actions in the lives of the two men involved—so many that this one document deserves two QuickLessons from us: one for analysis and one for planning future research.

Surface Level: The Actual Words

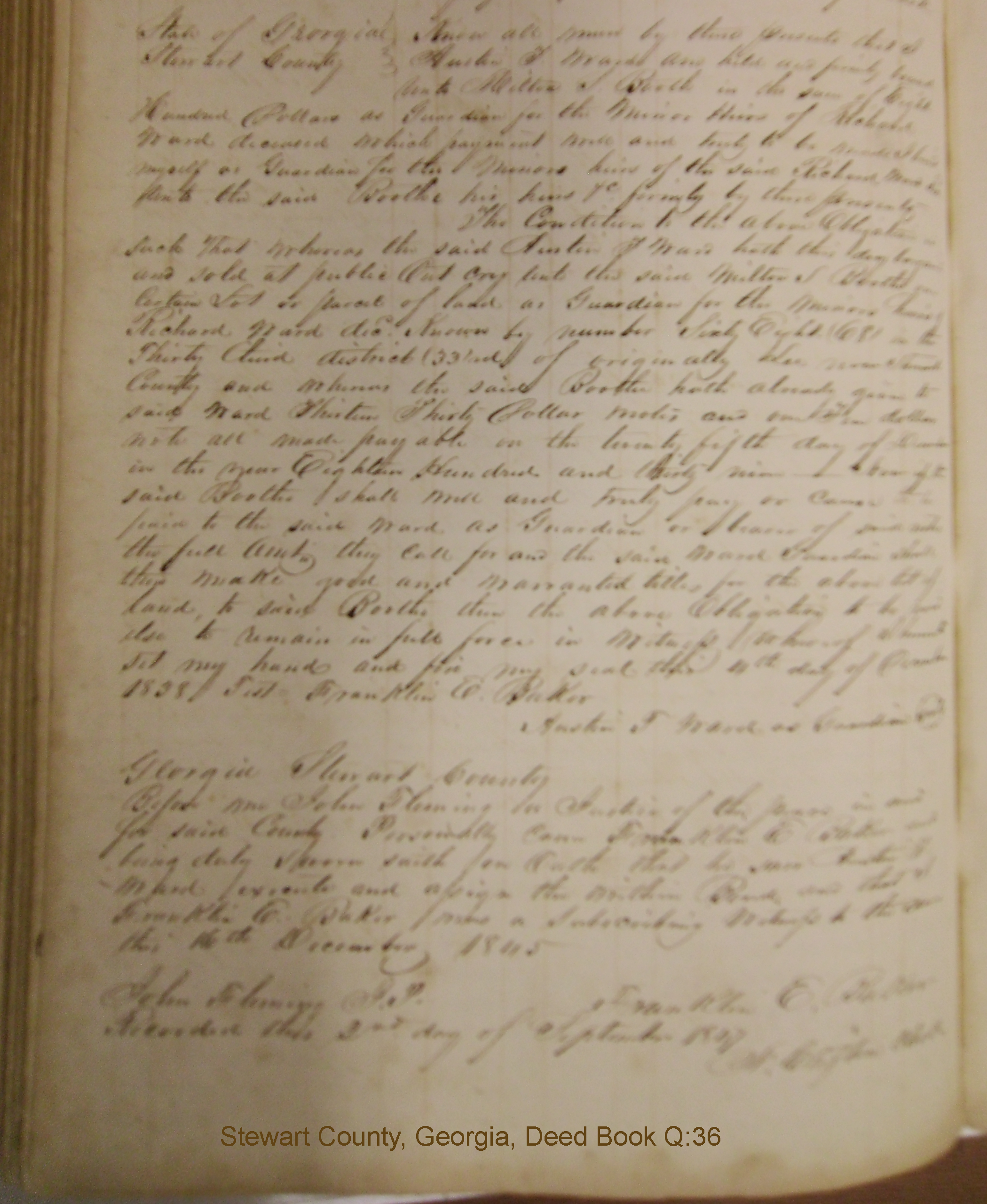

State of Georgia. Stewart County. Know all men by these presents that I Austin T. Ward am held and firmly bound Unto Milton S. Booth in the sum of Eight Hundred Dollars as Guardian for the Minor Heirs of Richard Ward deceased[,] which payment well And truly to be made[,] I bind myself as Guardian for the Minor heirs of the said Richard Ward decd Unto the said Boothe his heirs &c [etc.] firmly by these presents. The Condition to the above Obligation is Such that Whereas the said Austin T. Ward hath this day bargained and sold at public Out cry unto the said Milton S. Boothe a Certain Lot or parcel of land as Guardian for the minor heirs of Richard Ward decd Known by the number Sixty Eight (68) in the Thirty third district (33rd) of originally Lee now Stewart County and whereas the said Boothe hath already given to said Ward Thirteen Thirty Dollar notes and one Ten dollar note[,] all made payable on the twenty fifth day of December in the year Eighteen Hundred and thirty nine—Now if the said Boothe shall well and truly pay or cause to be paid to the said Ward as Guardian or bearer of said notes the full Amt. they call for and the said Ward Guardian shall then make good and warranted titles for the above lot of land to said Boothe[,] then the above Obligation to be void[,] else to remain in full force[.] in Witness whereof I have set my hand and fix my seal this 4th day of December 1838. Test [teste—i.e., the official witness] Franklin E. Baker. [Signed] Austin T. Ward as Guardian {Seal}

Georgia. Stewart County. Before me John Fleming a Justice of the peace in and for said County[,] Personally came Franklin E. Baker and being duly sworn saith for Oath that he saw Austin T. Ward execute and assign the within Bond and that the said Franklin E. Baker was a subscribing witness to the same. [Signed] The 16th December 1845. Franklin E. Baker. John Fleming, J.P.

Recorded this 2nd day of September 1847. —— [Name of registrar or clerk, illegible]1

Beneath the Surface: The Legal Layers

Re: The record

The document itself is a performance bond, otherwise called a bond for title. Although it appears in a deed book, it was not created to convey ownership of the land. It merely promises to do so, if certain terms are met.

Re: The guardianship

Despite modern definitions of this quite-ordinary word, we would err if we assumed that Richard Ward’s minors, after his death, were being reared or “cared for” by a “guardian.” We would also err if we assumed that Richard Ward’s wife had also died—thereby creating a need for a custodial guardianship. Indeed, we might err if we presumed that the heirs were Richard’s own children.

Courts of that era appointed guardians only when minors inherited money or property. Because inheritances were involved, the underlying records should exist in proceedings of the probate or orphan’s court—for Stewart County: the Ordinary Court. However, the court-appointed guardianship covered only financial matters, not the management or care of the children. Propertied minors without a living or capable parent might also become the legal ward of the guardian, but that status typically required a separate legal action—which would mean additional records for a researcher to seek.2

Unpropertied minors, in that society, were not assigned guardians. If a surviving parent (i.e., their natural guardian) could not support them, financially or logistically, or if they had no living parent, they would be bound out to labor for their living until their twenty-first birthday, the age of legal adulthood. That binding out would also be underpinned by at least one court action, and a surviving record might appear in court proceedings other than probate matters.3

Guardians were routinely appointed for minor heirs whose mothers were very much alive. Women in this society were less likely to be educated or conversant with laws of inheritance or guardianship. When a feme sole (a woman with no living husband or one whom the courts allowed to manage her own affairs as though she had no living husband) accepted the financial guardianship of minor heirs, she would lose that status upon remarriage. As a wife (a feme covert) her legal identity became that of her husband. The court might then assign her guardianship role to that new husband or appoint some other male.4

Odds do favor an assumption that the heirs were Richard’s own children; but accurate historical interpretations are based on specifics, not odds. Alternate situations also occurred. The unnamed heirs might be Richard Ward’s grandchildren, the offspring of a son or daughter who predeceased Richard. Indeed, Richard Ward might have died childless. If he never married and left no legal offspring, his heirs would be his siblings—some of whom could well be minors, depending upon Richard’s age—or they might be the children of his deceased siblings.5

The only justifiable conclusions from this document, insofar as Ward relationships are concerned, are these:

- Richard Ward died prior to 4 December 1838.

- He left a joint ownership in a tract of land to at least two individuals under the age of twenty-one and possibly others who had already reached their majority.

- Whether those minors were forced heirs (those dictated by law when property owners died without a will) or whether Ward left a will that named his heirs is undeterminable from this record.

Re: The property

Austin Ward’s bond tells us that an auction (likely an estate sale) was held on 4 December 1838. It tells us that Boothe was either the highest or only bidder. Because Boothe gave promissory notes obligating himself to pay the amount he had bid, he would have been allowed to take custody of the lot. As with modern home mortgages, he would not hold title to the lot until and unless that debt was paid in full. If the payment was not made by the specified date—one year and three weeks from the day of the auction—Boothe could be evicted.

The property is described as a lot. Again, researchers should not apply the modern popular concept of that term: that is, a relatively small plot of ground in an urban setting. Georgia adopted a rectangular survey system in the early nineteenth century. Unlike the rectangular system used for federal lands, Georgia did not identify its tracts by township, range, and section. Instead it used the terms districts and lots, and a standard lot was set at 202.5 acres.6

Contrary to assumptions earlier researchers have made from the first paragraph of the document, the price of the land was not $800, of which $400 was covered by those notes and the remainder “obviously” paid in cash. The price was exactly $400. The initial reference to $800 reflects a provision common in American law of that era: When posting a performance bond in a matter that involved property, the value of the bond was typically twice the value of the property involved.7 The doubling of the value created a stiff penalty for the bond’s signer, if he or she did not fulfill the stated obligation.

Ward drafted the document himself, informally, without benefit of an attorney, notary, or (as was more common in their society) a justice of the peace. Had the document been created by an officer of the court, the text dated 4 December 1838 would have carried the legal certification of that officer in a paragraph similar to the text for 16 December 1845.

As it stands, Ward’s rudimentary knowledge of legal language adds to the ambiguousness of the document. His do-it-yourself approach spared him the fee he would have paid for legal assistance, a not-at-all uncommon practice in his society. It was also one that created legal difficulties in the years ahead.

Other Contextual Layers

Financial straits

Austin Ward’s document speaks in many ways to the dire economic times that existed in the years spanned by this document. A worldwide financial crisis in 1837 bankrupted millions of men. Property prices collapsed after years of rampant speculation, primarily in real estate. Business and industrial enterprise would remain depressed through the mid-1840s. Boothe’s 1838 offer to buy Lot 68 on credit, with no cash downpayment, was likely the best offer that Ward could get.8

The fact that Ward accepted those terms suggests that the minors were financially in need. Holding onto the property while “riding out the downturn” was not a viable option. Those terms would have been quite uncommon in normal times. A typical credit sale of property in the nineteenth century called for repayment over three-to-five years, with one reasonably large note due each year.

Ward’s requirement that the debt be paid within a year, via fourteen separate notes due on the same day, was a wise provision. Promissory notes could be used as financial tender when bank notes and coin were scarce. A riff of small-denomination notes would allow Ward to meet financial emergencies for the minors, while selling off only as much as needed. That was a critical concern, because those who bought the notes would expect them to be discounted. Finding someone to take a single $400 note would have been a chancy proposition and the discount would have been steep.

Ward’s decision to break down the debt into notes of $30 or less also demonstrated some knowledge of the law. Under Georgia's prevailing statutes, any prosecution of an unpaid note, bond, or debt greater than $30 had to be taken to the taken to the county superior court. Small debts of $30 or less could be prosecuted more quickly before a local justice of the peace.9

Mishaps

Allison’s search for records created by Boothe, her person of interest, generated one other find:

20 January 1841, Columbus Enquirer, Muscogee, Georgia

Pocket Book Lost. Lost on the 7th day of December 1840 in Elbert county, the following thirty dollar notes for $390 and one of $24 [sic] on Milton S. Booth [sic] and John M. Wright, security, made payable to Austin T. Ward or bearer, and due the 25th day of December 1839. ... All persons are hereby cautioned against trading for the above described notes, and those who gave or signed them are hereby forewarned against paying them to any other person other than the subscriber, who is the only proper owner. [Signed] William G. Ward.

Boothe’s debt had not been paid when it fell due. In the meanwhile, at least two other events had occurred. First, Austin Ward had assigned the bond and the notes (i.e., signed them over to someone else, for cash or in settlement of sums owed). Second, Austin Ward or his assignee, William G. Ward, had extended Boothe’s credit, rather than launching an eviction process. The new note for $24 would typically represent the addition of interest on the unpaid debt. Given the lack of a mention to the old $10 notes, one of three options likely happened. Boothe may have paid one of them; the Wards may have assigned one to someone else for cash; or Boothe may have combined the $10 note with $14 interest to create the new $24 note. In any event, the addition of a “security” not named in the original bond reflects the bondholder’s concern as to whether Boothe would eventually be able to pay. In the event that he did not, then John M. Wright would be liable for Boothe’s debt on any note he cosigned.

A Legal Game-change

William G. Ward’s carelessness had significance for both the Wards and Boothe. The Wards still held the 1838 document, but Boothe was in possession of the land—albeit without a valid title. The 1838 bond itself had obligated only Austin Ward, while Boothe’s signature existed only on the notes that were now lost. If those notes were not recovered, the Wards had limited legal recourse. Recouping their loss without incurring legal costs would depend upon Boothe’s personal integrity. If Boothe claimed that he had already paid the debt, William Ward would have to prosecute a suit against him to recover the property.10

The eventual 1847 filing of the 1838 bond indirectly attests that the legal difficulties had been settled. The fact that Austin Ward did not, at that time, make over an actual title to the land suggests that he was no longer around to do so or that he no longer held the legal authority to grant that title. The affidavit made before a justice of the peace in 1845 by Franklin E. Baker, attesting that he had witnessed both the execution and the assignment of Ward’s bond, suggests a likelihood that the Ward-Boothe affair was settled at that time. The nearly two-year delay between that affidavit and the legal filing of the surviving document was a circumstance often seen in their society. Legal filing required the payment of a fee. Particularly amid financial distress, that legality was often postponed until new circumstances impelled it.

BOTTOM LINE

Whether the Ward-Boothe affair was settled amicably or by court action cannot be determined from the two known records. But, together, the pair lay out a rich trail of clues pointing to at least two dozen other possibilities to explore. QuickLesson 6 will use these clues to illustrate a useful tool for historical researchers: mindmapping.

2. Thomas R. R. Cobb, ed., A Digest of the Statute Laws of the State of Georgia in Force prior to the Session of the General Assembly of 1851, vol. 1 (Athens: Christy, Kelsea & Burke, 1851), 281–347, details the laws that governed guardianships during the years spanned by this document; accessible via Google Books (Books.google.com).

3. Ibid., specifically 284, 313, and 346.

4. Ibid., 327. Guardians might also be appointed for minor heirs whose fathers were alive. See for example, page 322.

5. For heirship eligibility, see especially the “Table of Descents” on unnumbered page 290.

6. Farris W. Cadle, Georgia Land Surveying History and Law (Athens: University of Georgia Press) is an essential work for understanding Georgia’s land and its settlement; chapter 4 provides a core description of the survey process.

7. Similarly, someone who purchased mortgaged property was obliged to post a bond of twice the value of the property, guaranteeing that they would not “alienate” the property before the mortgage was cleared; see Cobb, Digest, 513.

8. The most current historical analysis of this financial crisis is Alasdair Roberts, America’s First Great Depression: Economic Crisis and Political Disorder after the Panic of 1837 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2012).

9. Cobb, Digest, 638–39.

10. Ibid., 513–14.

How to cite this lesson:

Elizabeth Shown Mills, “QuickLesson 5: Analyzing Records,” Evidence Explained: Historical Analysis, Citation & Source Usage (https://www.evidenceexplained.com/content/quicklesson-5-analyzing-records : [access date]).