Elizabeth Shown Mills

1. Those records were never created in the first place.

Recordkeeping is so commonplace today that our expectations are often skewed. Children are born with a birth certificate aren't they—a peel-off form on their chest, ready for the doctor to fill out and file? We think no one is allowed to die without a death certificate. And everybody got married, at least before our modern change of manners.

So we think. But the past did not work that way. Yes, Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay Colonies mandated birth registrations almost from their founding; but most American states did not mandate them until the twentieth century. Many states, pre-1900, did not require that land sales be recorded in the local courthouse or town hall. Few people left wills; and states, for much of the past, did not require a probate process when there were no creditors and only one legal heir—or when the heirs amicably settled matters between themselves.

2. Records were kept, but your person-of-interest never created one.

A poor, honest man or woman—or one living on a frontier—could go a lifetime without visiting a lawyer, judge, or justice of the peace to create a legal record. If a man’s youth fell between wars, he may never have done military service. To find low-profile people of the past in surviving records, we have to devise strategies for finding what they, themselves, did not create.

3. Records were kept, but have been destroyed.

Fires, floods, vermin, wars, and windstorms have all taken their toll, even under the best of conditions. So have short-sighted county officials with planned-destruction (er, record-retention) policies. Clerks short of space in their record rooms have consigned older records to basement crawl spaces or leaking outbuildings, until mold created a health hazard and it was no longer “safe” to keep them.

Even so, copies may survive. For annual tax rolls destroyed at the county level, we may find the state-level copies at the state archives, in the records of the state treasurer or auditor. For older counties whose periphery was cut away to create newer counties, we may find early records in those offshoots—sometimes original record books that were carried off by the new officials, sometimes transcripts laboriously hand-copied by the new officials to document ownership of the lands in their new county. When local court cases were appealed, copies would be made of the documents in the local case and sent to the higher jurisdiction. The district-court files may be in a different county from where the county-level case was heard. The state appeals court files are typically at the state archives or a state supreme court library.

Even within the worst of the “burned-out” counties, we can find post-destruction records re-recorded from privately-held documents. For colonial and antebellum lands whose patents and deeds were not locally recorded at the time the property transfers were made, twentieth-century registers may yield copies of those documents tardily recorded or reconstructed by attorneys attempting to prove a title by modern standards.

4. Records were kept, but your person-of-interest seems to be omitted.

Censuses are the prime offenders here. Prior to the automobile age, the generally poor state of roads meant that many rural families were missed. Conditions in urban environments may have discouraged enumerators from visiting certain neighborhoods. Language barriers existed in ethnic enclaves, both urban and rural, causing names to be garbled beyond recognition. Prior to 1880, federal census takers were required to make multiple copies—two to three each census year; beginning in 1830, copies were supplied to district-court clerks or state offices in addition to the Census Bureau. In the process of making those copies, both individual names and whole pages were omitted and names were reduced to initials. But the fact that multiple copies were made gives us alternate opportunities for state and local copies, when the commonly-used federal census does not fill our need. From 1850 to 1880, multiple schedules were made each census year, in addition to the basic enumeration of population. Those agricultural, industrial and manufacturing, mortality, mining and fishery, slave, and social schedules offer opportunities to find individuals not listed on the basic population schedule.

5. Records were kept, but they grew legs and walked off.

Before Chester Carson invented the Xerox process, attorneys often “checked out” records from the local record office and then forgot to return them. Researchers who make a practice of (a) identifying all the attorneys for the place and time of their study and (b) searching for papers of those attorneys in manuscript guides such as NUCMC (National Union Catalog of Manuscript Collections) can be richly rewarded. Other record books and files missing from local courthouses and town halls can be found at local libraries, university archives, and state archives. In some cases, these were officially placed in the library or archives for safekeeping. In other cases, documents unofficially removed from the record offices were later donated to an archive by those who had taken them—or by their descendants; these are most-often found in collections bearing personal names.1

Bottom line.

When alternative sources and auxiliary repositories don’t yield the direct evidence we seek to resolve our research question, many possibilities still remain—if we shift our mindset. Instead of deciding The records I need just aren’t there, it’s time to ask How can I better use the records that do exist? 2

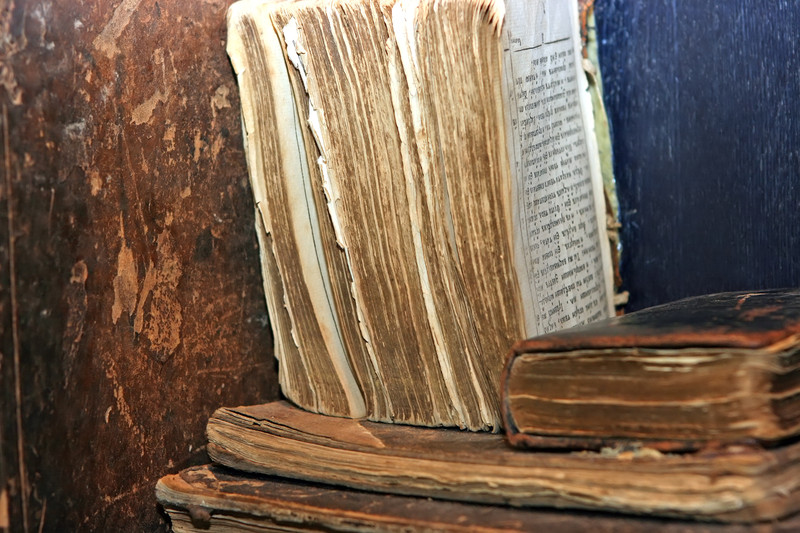

PHOTO CREDITS: "Old Books," CanStockPhotos (http://www.canstockphoto.com/images-photos/old-books.html#file_view.php?id=1337895: accessed 3 December 2015), csp1337895, uploaded by Siart, 27 November 2008.

1. As a case at point for the disappearance of local records, along with alternate sources and places to study, see the tutorial created by Elizabeth Shown Mills for Natchitoches Parish, Louisiana, posted as “Bits of Evidence” Nos. 468–482 at “The Forgotten People: Cane River’s Creoles of Color,” Facebook (July 11–29 August 2015).

2. For examples of these strategies, see QuickLessons 7 ("Family Lore"), 11 ("Identity Problems and the FAN Principle"), and 16 ("Speculation, Hypothesis, Interpretation & Proof").

of course

Thank you for the great idea - the packet for my 5th great grandparents' divorce in 1803 is lost. But the wife's great uncle was a rather well known person who was then Chief Justice of the R.I. Supreme Court (where the divorce was granted). I always figured he made the papers "disappear" - never thought of making sure I know all about the papers he left behind. Thank you!!

Good luck there, Diane!

Good luck there, Diane!

Missing files

One file I hired a researcher to find was missing from the courthouse. This really bugged the researcher. After a few days, the researcher had a dream, and was able to locate the file on microfilm at the local Historical Society. It was a hundreds-of pages estate file. The original may have been tossed in a box of stuff to be returned to the Courthouse, but never grew the requisite legs for the return trip . . . .

Good hunting to all,