Elizabeth Shown Mills

As researchers, we use words so loosely. Too loosely. We speak of the marriage record as though just one record existed. We cite a date of marriage from a courthouse index without questioning which marriage-related event actually occurred on that date. In fact, we even see dates of marriage cited for couples who never went through the ceremony after one of the preliminary records was created.

(Should I confess here that I speak here from personal experience, of a sort? Two different marriage licenses exist for my own nineteen-year-old mother—both issued the same week in different counties: one for the man she planned to marry and one for the man her parents wanted her to wed. The latter was a ruse that actually worked. She “faked off” her parents by going to the courthouse for a license with Edward, so they wouldn’t suspect her plan to run off with Earl.)

What about you? When you see a database of “marriage records,” do you question whether the date, presented so matter-of-factly, represents an actual marriage or a license that was never used? Even when you know the marriage occurred, have you sought all the records that may have been created for that event—each of which called for different types of information?

Traditionally, in what is now the United States, civil marriage registrations began (in some areas) with the filing of an intent and in most areas with the purchase of a license. Before the twentieth century, as a rule of thumb, it also required the signing of a bond ensuring that the parties were legally qualified to marry.

Typically in those quaint days, only the groom and his bondsman visited the courthouse or the town hall to get the license. If the bride was not of legal age and his bondsman was not her parent or guardian, the groom might bring with him a consent penned by the bride’s parent or guardian, assuring the clerk that the bride had their permission to marry this particular man—or one forged by the bride or another accomplice. Those intents, bonds, and permissions—as well as copies of the licenses—would then be maintained by the town or county clerk. Or at least they should have been.

In some regions of early America, couples also created marriage contracts, itemizing the property and cash savings each was taking into the marriage—along with the terms under which property would be divided, if and when the marriage was dissolved by death, divorce, or separation. These records, usually drafted by the neighborhood notary or justice of the peace, might stay in the notary’s office until such time as the marriage dissolved. Or, the j.p. might file a duplicate copy with reasonable promptness—with the clerk who recorded property records, not the one who recorded marriages.

Meanwhile, the marriage license issued by the court clerk was typically given to the groom, who then surrendered it to the minister or civil official when the ceremony occurred. That official was responsible for returning the license to the court clerk, with details about the ceremony he had performed: time, place, and parties involved.

By the late-nineteenth century, in many corners of America, that license issued to the groom carried a preprinted bottom section for the minister or other designated official to fill in the marriage details. This part of the form was sometimes called the minister’s certificate, in the sense that the officiating party was certifying the facts. This “certification,” returned to the court by the minister or civil official should not be confused with modern certificates of marriage issued by today’s clerks who are certifying that a record is on file.

Whatever the form in which the officiating minister or justice filed his report of the marriage, the court clerk would then, by law (unless he ignored it), record the marriage return. In some locales, only the returns were entered into registers by the town or county clerk. In other locales, the clerks maintained registers that included licenses issued, whether or not a return was filed. These are the ones that lead us so astray when they are entered into databases and we assume the existence of an entry means the marriage occurred. Many clerks, bless them, also retained the loose bonds and licenses—some of which contain much more information than the details extracted into the marriage register.

As states began to require formal registration of all vital events, copies of the marriage returns were also forwarded to a designated state agency—which now respond to record requests by supplying state-level certificates attesting the basic details. But, then, not all local clerks made the effort to submit all records—which means we cannot trust that a search made by the state agency, or a search we make of a wonderfully handy state-level database, actually includes the set of records in which our needed one would have been filed.

Are you rethinking, now, this whole issue of marriage records and what it is you actually have for this person whose life you are trying to reconstruct?*

*EE, of course, provides models for citing all these different types of records, amid all the quirks and vagaries of yesteryear’s recordkeeping systems.

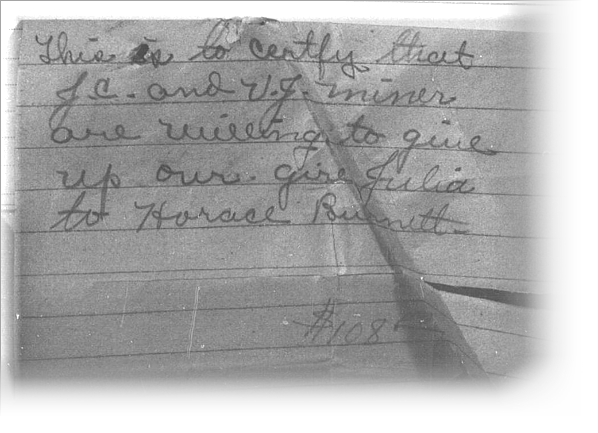

DOCUMENT IMAGE: Cullman County, Alabama, Marriage Book 15: 40, parental permission for Julia S. Miner to marry Horace W. Burnett—attached to clerk's register recording the license, bond, minister's return, and required doctor's certification that the groom was free of venereal disease; imaged in "Alabama County Marriages, 1809–1950," database, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/pal:/MM9.3.1/TH-1971-34755-29023-40?cc=1743384&wc=M6TG-D2S:134169601 : 29 March 2015).

Posted 30 March 2015

Marriage-related items

Oh, this is such an on-target reminder.

For one of my ancestral couples I have a Town Clerk's entry of date of publication of intention to marry, and the same Clerk's dated certification (a few weeks later) of publication and date, but no marriage return found.

Unfortunately, a respected genealogical journal published the date of publication, which has been picked up in numerous trees as the marriage date.

Happily, the Town Clerk in the Town they moved to entered a family record giving both persons' full names. While the date of ceremony was not given here, at least there is evidence that the marriage was considered to have taken place by the parties.

So attached to to your warning to sort out the sort of record actually found is yet another cautionary note to beware of indexes and extracts.

Thank you,

Kimberly Powell takes our

Kimberly Powell takes our Analyst of the Week prize for her Facebook comments on this Alabama document test (marriage permission? sale of daughter? sale of slave? adoption?). Rather than looking at this one 'parental note' in isolation, Kimberly scanned pages of the record book, before and after this one, and made an interesting discovery. I'll post her comments here so you won't have to scrounge back through the pile of messages on EE's Fb page.

"Elizabeth, you sucked me in with this ... I noted similar permissions tacked onto other marriage records in that volume that appear to have possibly come from the same note pad. It spurred visions of a cluttered desk, a grubby scratch pad, and an amount scribbled at the bottom of a page by Mr. Buchanan that relates to some other business of his very busy office! There appears to be a word following the amount but I can't make it out. I thought maybe something that had bled through since it is lighter, but it still seems a bit too clear for that. It also appears as if it may have been folded just above that notation, and was possibly originally folded up behind the note and escaped over time."

For those of you who haven't had time to scan the record book for context, after you click the link in the footnote above, you'll find a sampling at images 33, 35, 52, 56, 58, 61 and—a double slam—at image 63.

So ... how many of you, in the research process, would image that one page for the one record of interest, assume that the handwriting was that of one of the parents, and proceed blithely on your way back into the past with a basic misassumption and a host of curiosity-driven speculations about this 'parental note'? (And, no, you don't have to actually answer us in this forum. The question is just a thought-provoker.)