Petitions to the president. Petitions to Congress. Petitions to the governor. Petitions to the legislature. Petitions to mayors and local commissioners. Petitions can be found at almost every level of government. As students of history, how do we use these? What value do we squeeze from them? Do we systematically seek them? Or, do we occasionally stumble upon one that has a name of interest and think: Hmhh, could this be my person-of-interest?

For 797 years the English legal tradition has guaranteed citizens the right to petition those who govern them and to plead for redress of whatever wrongs they perceive. The rich and the lowly have both exercised that right, as individuals and in groups. They have petitioned for citizenship and divorce, for statehood and county divisions, for freedom from slavery and protection of religious liberty, for the improvement of roads or rivers and the incorporation of towns, for clemency or pardon from all kinds of convictions, for pensions and payments for services rendered, for relief from taxation or reimbursement for losses blamed on government action—or otherwise alleviate hardships, make wrongs right, or grant personal favors.

Students of history tend to discover these petitions in one of two ways. The modern preference is to Google or Bing a search topic―or, perhaps more systematically, to query a database created by a state archive.1 More traditionally, researchers have turned to published government documents such as the U.S. Serial Set2 or Clarence Edwin Carter’s classic series Territorial Papers of the United States.3 These selected records from the holdings of various public agencies, tidily abstracted or transcribed and indexed, simplify our searches for insight into the lives of Americans of yore.

So, we find a petition. What, then, do we do with it?

Case at Point

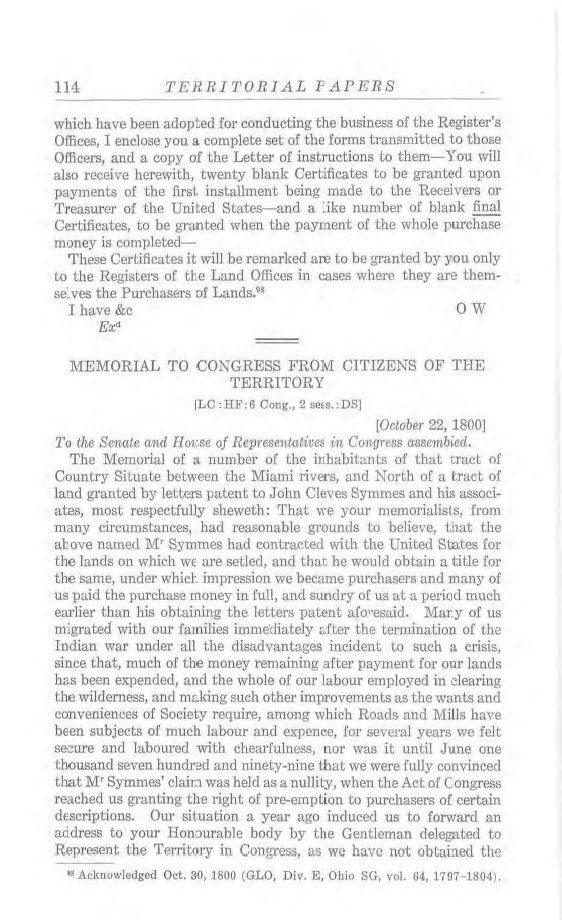

On 22 October 1800, 336 men and 1 widow living in southwest Ohio signed a petition addressed to the U.S. Congress. They detailed their suffering. They stated the cause of their grievance. They asked for assistance. They all signed or had someone do it for them. If Carter’s transcription can be believed, they were all literate—every last one of them—a highly suspect situation on any frontier.4

The petitioners supplied no personal identification other than their names, thereby leaving only those signatures to distinguish them from other same-name people—or so we assume. They provided nothing to identify the locations of their residences, other than a broad reference to being “between the Miami rivers and North of a tract of land granted by letters patent to John Cleves Symmes.” What we have to work with, superficially, are 47 lines of ponderous text about a collective experience and 8 typeset columns of names.

Historians can mine this document at two layers: (1) surface nuggets picked up from Carter’s easy-to-use derivative; and (2) subsurface extraction from the original document itself.

Layer 1: The Published Typescript

The grievances set forth by the petitioners offer several tidbits of value: clues to the period in which they settled Ohio’s frontier, the region they settled, and the hardships they endured.

TIME FRAME OF ARRIVAL

"Many of us,” the petitioners wrote, “migrated with our families immediately after the termination of the Indian war."

With historical context, we can develop this one sentence into a meaningful chapter in the lives of the petitioners. To briefly outline it here: For a dozen years following the American Revolution, conflict roiled the Old Northwest. By the Treaty of Paris, 1783, Great Britain ceded its claims to the region and federal authorities proceeded to organize those distant lands according to their own design.

Predictably, indigenous tribes resisted. For the Euro-Americans who attempted to settle the two new territories north and south of the Ohio (the point-of-view of this particular petition), the conflict was brutal until General “Mad” Anthony Wayne crushed Native American resistance at the Battle of Fallen Timbers. After the 3 August 1795 Treaty of Greenville officially ended hostilities, newcomers poured into Ohio from Kentucky, Virginia, Pennsylvania, and the Northeast.5

On a frontier without courthouses, land offices, schools, newspapers, and other record-creating institutions, surviving threads of a human life are often too scarce to weave into anything of substance. From this bit of context, however, we can begin to set the stage on which these individuals acted. As a starter, this petition enables us to narrow to a five-year time frame—August 1795 to October 1800—the period in which many of those families arrived in Ohio.

But where, in Ohio, did they stake their lives?

LOCATION

The preamble to the petition provides a general location:

"The Memorial of a number of the inhabitants of that tract of Country Situate between the Miami rivers, and North of a tract of land granted by letters patent to John Cleves Symmes and his associates."

Here, context not only narrows our focus but also expands our opportunities for more records of value.

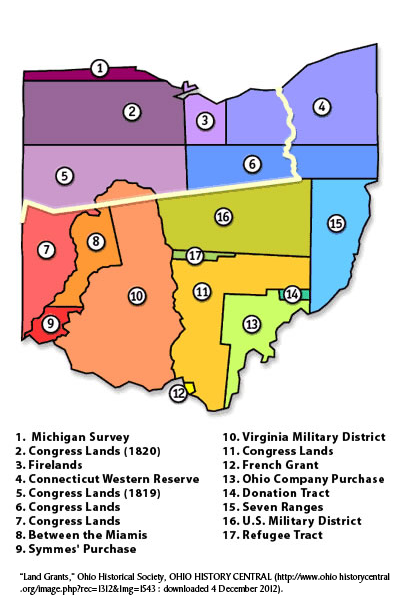

In the wake of the Revolution, dozens of well-connected Americans organized land companies and persuaded Congress to allow them vast tracts of the public domain by which they might build their personal fortunes. In return they promised to populate those lands with settlers, to whom they would sell small parcels at a substantial profit. One of those entrepreneurs was Judge John Cleves Symmes, a U.S. Congressman from New Jersey.

In 1787, he petitioned his colleagues in the House to set aside for his new “Miami Company” a million acres—roughly all the land lying between Ohio’s Little and Big Miamis.6

Symmes’s Purchase created the woes reported in this 1800 petition. His surveys were inept and his business practices a boondoggle. The actual patent signed by President George Washington in 1794 reduced Symmes’s acreage to less than a quarter of the domain he requested. Nonetheless, he continued to sell land well outside his allotted bounds, and many buyers discovered that the parcels they bought had been sold to others as well.7 The map at right marks the area legally allotted to Symmes as Region 8. Region 9, lying to the north of Symmes, is the area in which our petitioners had settled.8

AUXILIARY RECORDS

Despite the money paid Symmes by his victims, these men and their families had no legal claim to the lands on which they toiled. They were, in fact, doubly victimized, as their petition pointed out:

"Much of the money remaining after payment for our lands has been expended, and the whole of our labour employed in clearing the wilderness, and making such other improvements as … Roads and Mills." 9

Improvements notwithstanding, the settlers were squatters on the public domain and could be displaced by anyone who legally filed for their tract with the U.S. Land Office. By June 1799, they had recognized their predicament and had sought redress in the age-old form: a petition to Congress. Lines 22–30 of the 1800 petition alerts us to an earlier document:

"Our situation a year ago induced us to forward an address to your Honourable body. … We have not obtained the relief we prayed for in that [plea] … but firmly relying in the equity and Bounty of Congress [we] trust that our case will be taken into consideration early in the ensuing Session, and that the question will be determined whether we can apply without further waste of time to Mr. Symmes for our titles or a reimbursement of our monies."

That earlier petition, which Carter also published, places the petitioners in Ohio's new Hamilton County and narrows more tightly the time frame in which many of the settlers uprooted their lives for the promises held forth by the land between the Miamis:

"Many of your Memorialists have Purchased since the Month of April 1797 and some of them since the commencement of the present year." 10

The 1799 petition also offers another angle from which to develop the lives of specific signers. When we compare the two petitions, even in their published forms, it is evident that many of the 329 in 1799 were among the 337 petitioners of 1800. However, we also see many differences. A few 1799 signers had likely died in the fifteen-month interval. Others may have been missed one time or the other, amid whatever canvassing was done to collect the signatures. However, the extent of the differences between the two petitions also suggest that other families had given up hope in that meanwhile and had returned to their former homes or moved on elsewhere.

Layer 2: The Original Document

Published transcripts are a convenient finding aid; but, if we rely upon them, we forfeit something valuable: embedded clues that are masked or destroyed in the process of creating the derivative. This 1800 petition clearly makes that point.

In comparing the two printed lists, 1799 and 1800, we note significant differences in the rendering of names. Certainly, many are misread. On the original of the 1800 list, for which the published version presents all individuals as literate signers, we also see blocks of signatures all penned in the same hand, thereby alerting us to situations in which specific individuals were not literate and to clusters of individuals who were likely found in each other’s company at the time their signatures were collected.

Our comparison of the 1800 printed list to the original images also spotlights radical differences in the arrangement of names. Some differences can be expected. They reflect a variety of circumstances under which signatures were acquired. In contrast to censuses, in which enumerators were suppposed to go from door to door, petition signatures were also (arguably, more often) collected at gathering places. Copies were taken to taverns, rural stores and trading houses, and the courthouse square on court days.

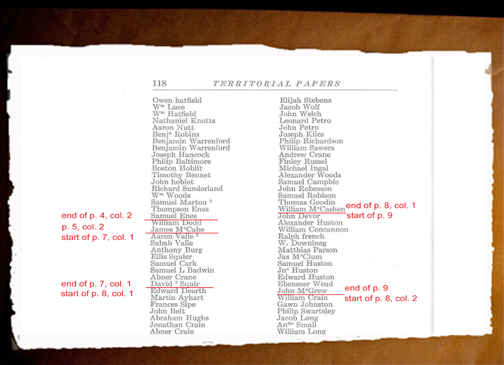

The publishing process also wreaked havoc with the natural order in which signatures were gathered. Working with printed pages of standard book sizes, transcribers and editors create page breaks that differ from the original. They make arbitrary decisions about flow from one column to another. Depending upon those editorial decisions, individuals of no proximity in real life can end up adjacent on the printed list. Kinsmen and neighbors who signed consecutively on the original, thereby silently attesting their connections, can be arbitrarily separated by dozens or hundreds of names in the published version. The published version of the 1800 petition commits these offenses, over and again, in its reshuffling of human lives.

Clarence Edwin Carter, the transcriber and editor of the Territorial Papers series, was considered a master at his craft. He actually wrote the National Archives’s official guide to the subject: Historical Editing, a work as valuable today as it was when published in 1952. There, Carter issues his own warning:

"The most expert typist is not always competent to transcribe handwritten documents exactly. From this fact stems one of the gravest problems of the editing and publishing of historical documents, for it is a truism that most textual corruptions are traceable directly to the transcriber."11

Carter adds suggestions for ways that transcribers can improve their skills. He lays out procedural rules to enhance quality. He also offers “exceptions from exact copy” that are permissible, in his opinion. While he is silent on the subject of transcribing lists per se, he does opine that “unusual spacing” within a document need not be reproduced.12

Carter also details the instructions that editors should give to printers who take the second-generation editorial copy and typeset it for the published work13—thereby creating the third-generation published copy we actually consult. Again, Carter offers no suggestion for the handling of long lists of names. Ostensibly, the only critical factor is that the names be thoughtfully transcribed and that none be omitted.

Woe unto all researchers who trust those good intentions!

CARTER’S TRANSCRIPTION vs. THE ORIGINAL

Carter’s edition presents the 1800 petition as 5.2 typeset pages. The original document,14 consists of 12 images on long sheets, as follows:

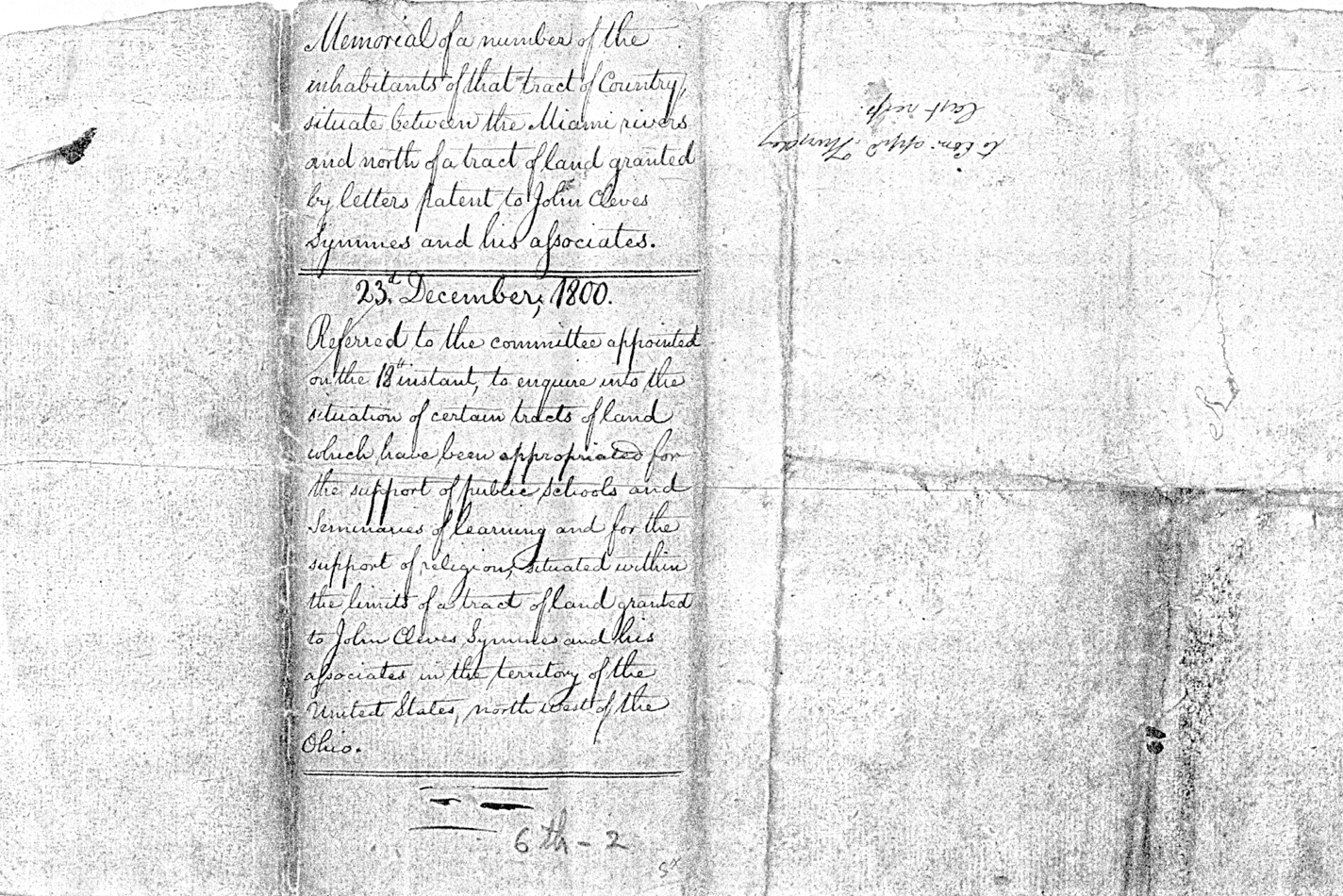

- A labeled wrapper for the bundle (shown above);

- The text of the petition, which constitutes a page and a half;

- Nine pages of signatures, some of which are organized into two columns.

In the comparison that follows, the term sheet will be used to signify a two-sided piece of paper. The term page will be used to signify one side of that sheet, as imaged.

Considering that the original document exists as loose sheets, it is impossible to determine the exact order in which the sheets were submitted to Congress. For the sake of comparison, the attached image file arranges the images—and numbers them—in the same order used by Carter’s typist. Within this arrangement, the first page of signatures is reasonably identified by the fact that it begins with a header: “Subscribers names.”

Comparing the original images with Carter’s typeset copy reveals radical differences in the arrangement of names. Those differences exist because Carter’s typist followed a practice different from that used by the original canvassers. Those variant practices can be broadly described this way:

Original Document

Each canvasser was typically armed with (a) a display copy of the “plea” that would go to Congress; and (b) at least one sheet of paper on which to gather names. Signers typically adhered to columns. After column 1 was filled, they proceeded to the next. If one side of a sheet was completely filled, subsequent signatures would be carried over to the reverse. Not until the reverse side was filled, as a rule, would a particular canvasser create a second sheet. On frontiers such as this one, paper was neither abundant nor inexpensive. It was not wasted.

For researchers who study individuals in social context in order to accurately identify them, the pattern matters. Adjacent names often represent those in physical proximity. In community canvasses, they were likely to be neighbors and kin. When signatures were sought at a “gathering place,” adjacent names can imply physical presence at the same place and time. The last individual who signed at the end of a page may well be connected to the first individual who signed at the top of that sheet’s backside. The name that falls at the end of column 1 will often carry some connection to the name that appears at the start of column 2.

The Published Document

Carter’s typist arbitrarily created a different pattern. On the image file inserted at this link, the published version is annotated to show the order in which the typist linked the names. The page and column numbers penned on the typescript represent the pages and columns from the original document. The order used by that typist is this:

- Page 1, column 1

- Page 2, column 1

- Page 3, column 1

- Page 4, column 1

- Page 5, column 1

- Page 6, column 1

- Page 1, column 2

- Page 2, column 2

- Page 3, column 2

- Page 4, column 2

- Page 5, column 2

- Page 7, column 1

- Page 8, column 1

- Page 9, column 1

- Page 8, column 2

As a consequence of this decision by the typist, individuals of no known connection or geographic proximity appear as consecutive “signatures” in the published version of the petition, while kin and neighbors are sometimes dozens or hundreds of names apart.

A physical analysis of the pages themselves also yields several discernible patterns that help us to reconstruct the order in which the names were originally collected.

- Pages 1 and 2 are the only two of the nine signature pages that are completely full, with no top or bottom margin. On both pages, a line was drawn down the middle. On page 2, that line was added after the signatures were gathered.

- Page 3 is reasonably full, with evenly balanced columns. However, the formatting—which uses wide margins at top and bottom and carries no dividing line between the columns—suggests that a different individual gathered the names on page 3.

- Pages 4–9 are only partially filled, with uneven columns or a mere partial column occupying a full sheet of paper—again suggesting that each represented the labor of a different canvasser.

- Page 6, which carries only 17 names, also shows the shadows of text written on the reverse. That mirror-image bleed-through and the ragged pattern of the sheet's edges both identify page 6 as the front side of the sheet used as the labeled “wrapper” for the petition—suggesting that it was, at the time of submission, the last sheet of the petition. As such, it could not be a continuation page for the completely filled pages 1 or 2.

- Page 7, which carries only 8 names, also shows the shadows of text written on the reverse—script that matches the signatures appearing in column 1 of page 1. From this we may deduce that the signatures appearing on pages 1 and 7 were the work of the same canvasser, who collected more names than the front side of his sheet could hold and then “carried over” the extra names to the reverse.

- Page 8, which offers a column and a half of names, has ragged edges that identify it as the backside of page 2. Again, these two pages seem to be the product of the same canvasser.

- Page 9, which offers only 12 names, also carries the shadows of names written on the reverse. That, together with the page’s distinctive edges, also identifies it as the reverse side of page 3.

All things considered, the physical analysis of the pages suggest that they likely represent the work of six canvassers. By extrapolation—for the purpose of identifying family and community ties—we might regroup these 327 individuals into six clusters:

- Community 1: Pages 1 and 7 64 signers

- Community 2: Pages 2 and 8 124 signers

- Community 3: Pages 3 and 9 62 signers

- Community 4: Page 4 43 signers

- Community 5: Page 5 28 signers

- Community 6: Page 6 17 signers

The Addendum to this QuickLesson transcribes the names in their original order, showing each name within its community cluster.

The Bottom Line

As researchers, we often are too trusting—especially when transcriptions are “officially” prepared (as in this case) or when they carry the imprimatur of an academic project (for example, any of the edited and published papers of early American presidents). We acknowledge the expertise of the project editors. We assume they have followed sound editing and transcribing principles.

The identity of this petition’s editor as the scholar who formulated standard principles for modern archival projects certainly gives us cause to trust the manner in which this petition has been presented. Is that trust warranted? Or has this QuickLesson reinforced for you the value of obtaining image copies of original documents for critical analysis rather than basing conclusions upon second– or third-generation derivatives?

1. As examples of valuable online databases that feature petitions:

- “Online Records Index,” South Carolina Department of Archives and History (http://www.archivesindex.sc.gov/onlinearchives/search.aspx).

- “Massachusetts Archives Collection (1629–1799,” Massachusetts Archives (

http://www.sec.state.ma.us/ArchivesSearch/RevolutionarySearch.aspx).

- “Legislative Petitions,” Library of Virginia (http://www.lva.virginia.gov/public/guides/petitions/index.htm).

- “Early Petitions to Congress,”The Robert C. Byrd Center for Legislative Studies (http://www.byrdcenter.org/index.php/resources/early-petitions-to-congress/).

(All online links in this QuickLesson were last accessed on 4 December 2012.)

2. “U.S. Congressional Serial Set: What It Is and Its History,” Federal Depository Library Program, FDL Desktop (http://www.access.gpo.gov/su_docs/fdlp/history/sset/index.html). Part of the Serial Set is available in a searchable online database at “U.S. Serial Set,” Library of Congress, A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774–1785 (http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/amlaw/lwss.html).

3. Clarence Edwin Carter and John Porter Bloom, The Territorial Papers of the United States, 28 vols. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1934–1975). Volumes 1–26 of this series are available as digital images online at The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, FamilySearch (books.familysearch.org).

4. Carter, Territorial Papers, vol. 3, The Territory Northwest of the River Ohio, 1787–1803, Continued (1934), 114–19.

5. For an overview of these frontier conflicts, see “Ohio Indian Wars,” Ohio Historical Society, Ohio History Central (http://www.ohiohistorycentral.org/entry.php?rec=527&nm=Ohio-Indian-Wars). For a more substantial treatment, see R. Douglas Hurt,The Ohio Frontier: Crucible of the Old Northwest, 1720–1830 (Bloomington, Ind.: Indiana University Press, 1996).

6. For an introduction to Symmes’s Purchase (aka Miami Purchase), see George W. Knepper, The Official Ohio Lands Book (Columbus: Auditor of State, 2002), 31–33; also“Symmes Purchase,” Ohio Historical Society, Ohio History Central (http://www.ohiohistorycentral.org/entry.php?rec=806); and Hurt,The Ohio Frontier, 160–66.

A list of manuscript collections that hold personal papers of John Cleves Simmes can be found at Biographical Directory of the U.S. Congress, 1774–Present (http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/guidedisplay.pl?index=S001137). Particularly note the John Cleves Symmes Papers, 1791–1846, in the Draper Manuscripts of the Wisconsin Historical Society. Also of value: The Correspendence of John Cleves Symmes (New York: MacMillan, for the Historical and Philosophical Society of Ohio, 1926).

7. The Congressional debates and acts that relate to Symmes Purchase (Miami Purchase) and the plight those who petitioned Congress can be tracked via the published government documents available online at the Library of Congress’s above-cited website, A Century of Lawmaking.

8. “Land Grants,” Ohio Historical Society, Ohio History Central (http://www.ohiohistorycentral.org/image.php?rec=1312&img=1543).

9. Symmes’s contract with each of his buyers required a minimum purchase of 160 acres. Buyers were to settle their land within two years of the purchase and remain on the land for at least seven years. Each was also charged additional fees for surveying and administrative costs; see Hurt, The Ohio Frontier, 164.

10. Carter, Territorial Papers, 3:29–35, particularly p. 30 for the quotation.

11. Clarence E. Carter, Historical Editing, Bulletins of the National Archives, no. 7, August 1952; reproduced as National Archives Publication No. 53–4 (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1952), particularly page 25 for the quotation.

12. Ibid., 27.

13. Ibid., 25–30.

14. This document, from RG 233, Records of the House of Representatives, has been provided by a NA technician, with the cryptic, penciled identification: "HR 6A - F14.3, 23 Dec 1800, Box 6." (The "1" in "F14" appears to be scribbled out.) It is imaged as part of NA microfilm publication M1707, Unbound Records of the U.S. House of Representatives, Sixth Congress, 1799–1801, 4 rolls (Washington: NARA, 1992), roll 4, frames 227–38.

ADDENDUM

Memorial to Congress from Citizens of the Territory North of the Ohio,

22 October 1800:

A Reordering of Petitioner Names into Community Clusters

Note:

For ease of comparison, this reordered list presents each name as interpreted by Carter’s typist. It corrects only the arrangement of the names. (It will also resist the temptation to add sic after many obviously mangled names.) Boldfaced names are those that would have been consecutive on the original but are arbitrarily divided in the published petition.

Region 1

Jno Crain [Start of original signature p. 1, col. 1]

John Barnett

John Patterson

Andrew Crean

Alxand Heart

John Hill

Jno King

Henry Marshall

Daniel Griffing

Henry Forgeson

Allexander Campbell

Wm Marshall

Joseph Crain

Robert Lefollet

Jonathan Robbins

Jno McCashin Jnr

Benjamin Ross

Jacob Petters

Jno H Williams

Robert woods

Geo: Livingston

Josiah Mott

Robert Ross

John Ross

James Keneer

Joseph Parks

John Robison Parks

Joseph Parks Jun [End of original p. 1, col. 1]1

Jams Trousdale [Start of original p. 1, col. 2]1

Thomas trousdale

Michael Auld

William Trousdail

John Bigger junr

William Stitt

David Buchanan

W Humphreys

James Pettiorew

James Aken

Benjamin Custard

Isaac Robins

Coonrod Custard

Isaac Van Nest

Jesse Watkins

Isaac Watkins

John Kritchel

Elisha Wade

Isaac Van Nest

Meeker Squier2

Moses Johnson

Cyrus Osborn

David Johnson

Richard Watts

John Watts

James Watts

Platt Dickson

Wm Owens [End of original p. 1, col. 2]3

Aaron Valle [Start of original p. 7, col. 1, being the backside of p. 1]3

Sabab Valle

Anthony Burg

Ellis Squier2

Samuel Cark

Samuel L Badwin

Abner Crane

David Squir2 [End of original p. 7, col. 1, being the backside of p. 1]

Region 2

Jas McCashen [Start of original p. 2, col. 1]

Samuel Everman

Stephen Welch

Aaron Richardson

James Small

Jacob Richardson

Robert Carrek

Abrm Glassmere

Alexander Woods

Danl Richardson

Nathaniel Blackford

Benjamin Daniells

John Rippey

Joseph Rippey

Jno Blair

Ephraim Blackford

Thon Kelsey

Jeremiah Blackford

John Blackford Jur

John Reed

Martha Bundle—widow

James Bundle

John Blackford

Benjamin Jones

Calvin Boll

Geo. Harlan Jnr

Aaron Harlan

William Mcdonal

Samuel Boyd

Jonh McDonel

James Boyd

William Boyd

Josepth hays

James Mcdonal

Eprraim Leorance Junr

Ephaim Leorance Ser [End of p. 2, col. 1]4

Fergus MCean [Start of p. 2, col. 2]4

Matias Balb

Isaac Linley

Adam Blair

John Gillis

Thoms Gillis

Martain Kever Ser

Martain Kever Jur

Peter Kever

Thomas Vinerd

Steven Venerd

Richard Luckey

Wilam Venerd

Richard Kirby

Vindle Piers

Zachariah Clearenger

job Clea(r)enger

Joseph Kirby

Michal wise

John Steveson

Jeams Steveson

Robard Reed

John davis

Joshua Carter

James Carter

James Stevinson

John Stevinson

Jonathan Garwood

Benjamin Kirby

Joseph Carter

Aron Biggs

Abraham luks

Thomas luks

Franses lukes

William graham

James Wislls

John richardson

John Buckhannon

William Richson

George lowry

Thomas Humphres

Jonathan Huggins

John Cook [End of original p. 2, col. 2]5

Edward Dearth [Start of original p. 8, col. 1, being the backside of p. 2]5

Martin Ayhart

Frances Sipe

John Belt

Abraham Hughs

Jonathan Crain

Abner Crain

Nimrod Devant

Giles Chaimbers

Bezebel Dearth

James Dearth Jun

Adam Null

Cristen Null

Charles Null

Thomas Davis

Elijah Stebens

Jacob Wolf

John Welch

Leonard Petro

John Petro

Joseph Kiles

Philip Richardson

William Sawers

Andrew Crane

Finley Russel

Michael Ingal

Alexander Woods

Samuel Campble

John Robesson

Samuel Robison

Thomas Goodin

William McCashen [End of original p. 8, col. 1]6

William Crain [Start of original p. 8, col. 2]6

Gawn Johnston

Philip Swartsley

Jacob Long

Andw Small

William Long

Fredrick Miller

David Short

Jno: Paul

Wm Paul

Jas Miller

James Craford

Wm Craford [End of original p. 8, col. 2, being the backside of p. 2]

Region 3

William Lamme [Start of original p. 3, col. 1]

John McClane

Jacob Miller

Allexander Barns

James Barns

Thomas Neal

Ephraim Bowen

James Snowden

James Collier

John Vance

Jacob Snowden

Joseph Vance

Nathan Lamme

Joseph Robinson

John Morgin

John Morgan

John Mattox

Abraham Henely

Charls Mcguire

Joseph McCard

Hennery Martin

Justis Luse

Elexander Mcooleuck

John Driskil [End of original p. 3, col. 1]7

Garret Rettinhouse [Start of original p. 3, col. 2]7

Samuel Freeman

Joseph mooney

Frederick Moslander

Leonard Leuchman

John Freeman

Wm Robins

John Judy

Jacob Judy

Martin Judy

Benjn Whiteman

Lewis Davis

George Allen

John Rettinghouse

William Allen

Owen Davis

Smith Gregg

Isaac Rubart

John Aiken

Joseph C. Vanie

Wm Kirkpatrick

John Wabb

John Scott

Benjn Kiser

John Kiser [End of original p. 3, col. 2]8

John Devor [Start of original p. 9, col. 1, being the backside of p. 3]8

Alexander Huston

William Concannon

Ralph french

W. Downineg

Matthias Parson

Jas McClum

Samuel Huston

Jno Huston

Edward Huston

Ebenezer Wead

John McGrew [End of original p. 9, col. 1, being the backside of p. 3]

Region 4

Benja Van Cleve [Start of original p. 4, col. 1]

John Folkerth

Thomas Chovea

Benjamin Dever

Jerom Holt

George Newcom

Danl Green

Jas Gillespie

Jeremiah Enes

John enes

Cyrus Sanett

Abraham Vaneaton

Jno Mcknight

Mathew Bolland

Samuel Berk

Samuel Berke

John Berk

Wm Venorsdol

Petter Sunderland [End of original p. 4, col. 1]9, 10

Joseph Whiting [Start of original p. 4, col. 2]10

John Bailey

Jno Luce

Andrew Bailey

Edward mitchel

Wm Sunderland9

Owen Hatfield

Wm Luce

Wm Hatfield

Nathaniel Knotts

Aaron Nutt

Benjn Robins

Benjamin Warrenford

Benjamin Warrenford

Joseph Hancock

Philip Baltimore

Boston Hoblit

Timothy Bennet

John hoblet

Richard Sunderland

Wm Woods

Samuel Marton

Thompson Enes

Samuel Enes [End of original p. 4, col. 2]

Region 5

John McCabe [Start of original p. 5, col. 1]

James Thomson

Job Westfall

Andrew Westfall

William Shaw

John Barnett

Abraham Barnett

William Westfall

Joel Westfall

Isaac Westfall

David Riffle

John Elles

George Adams

John Westfall

frederick Nuts

Bartholomew Berry

Albert Banta

Peter Banta

henry Atchison

John Quick

Abraham Hunt

John Gullion

Abratham Richardson

Antony Sheveler

Jeremiah Ludlo

Aron Richardson [End of original p. 5, col. 1]11

William Dodd [Start of original p. 5, col. 2]11

James McCabe [End of original p. 5, col. 2]

Region 6

John Ewing [Start of original p. 6

Robert Edgar

Richard Mason

John Vanarsdol

Nathan Talburt

Danniel Hole

Arial Coy

John Hole

Edmund Munger

Jonathan Munger

Thos Clawson

Peter Clawson

Benjamin Maltbie

Josiah Clawson

Samuel Foot

Mathew Bowling

John Clawson [End of original p. 6]

Notes to Addendum:

1. Carter’s published version misleadingly inserts 128 names between Joseph Parks Jun and Jas Trousdale.

2. As reconstructed, Meeker Squire, Ellis Squire, and David Squir are all in the same community. Meeker and Ellis are 12 signatures apart; Ellis and David have just 3 intervening names. As transcribed by Carter’s typist, Meeker and Ellis are arbitrarily separated by 105 signatures.

3. Carter’s published version inserts 94 names between Wm Owens and Aaron Valle.

4. The published version inserts 114 names between Ephaim Leorance Ser and Fergus MCean.

5. The published version inserts 59 names between John Cook and Edward Dearth.

6. The published version inserts 12 names between William McCashen and William Crain.

7. The published version inserts 135 names between John Driskil and Garret Rettinhouse.

8. The published version inserts 66 names between John Kiser and John Devor.

9. As reconstructed, Petter Sunderland and Wm. Sunderland are in the same community cluster, just 6 signatures apart. As transcribed by Carter’s typist, Petter and Wm. are 165 names apart.

10. The published version inserts 139 names between Petter Sunderland and Joseph Whiting.

11. The published version inserts 135 names between Aron Richardson and William Dodd.

How to Cite This Lesson

Elizabeth Shown Mills, “QuickLesson 14: Petitions—What Can We Do with a List of Names?” Evidence Explained: Historical Analysis, Citation & Source Usage (https://www.evidenceexplained.com/content/quicklesson-14-petitions%E2%80%94what-can-we-do-list-names : [access date]).